Table of Contents

Title I of the Healthy Forest Restoration Act (HFRA) of 2003 authorizes communities to draft and implement Community Wildfire Protection Plans (CWPPs). Community Wildfire Protection Plans (CWPPs) are local plans that are designed to specifically address a community’s unique conditions, values, and priorities related to wildfire risk reduction and resilience. Communities with CWPPs in place are given priority for funding of hazardous fuels reduction projects carried out under the HFRA.

A CWPP’s scale will determine the level of detail required for effective implementation. CWPPs can be developed for any type of community, such as neighborhoods, towns, fire protection districts, and counties. Information and level of specificity should match the plan’s scale. For example, county-level CWPPs are excellent “umbrella” plans for guiding priorities in smaller communities or county subareas, but typically do not provide the level of detail needed for reducing risk at a site-specific scale.

The Colorado State Forest Service (CSFS) works closely with communities across the state to support them in the development of their CWPP. CSFS also maintains a database of those communities with an approved CWPP and the year it was adopted or last revised. These CWPPs are available for download and planners are encouraged to view these examples to determine which CWPPs are in place within their local jurisdiction or county.

The 2012 Waldo Canyon Fire – Colorado Springs, Colorado

Understanding a community’s wildfire risk prior to an event not only guides appropriate action but also provides valuable information during and after a wildfire. On June 23, 2012, the Waldo Canyon Fire started approximately four miles northwest of Colorado Springs, Colorado. The fire grew quickly and within days thousands of residents were evacuated. Several neighborhoods within city limits were severely affected – in total over 346 homes were destroyed. The often untold story, however, is that many positive mitigation efforts were in place prior to the wildfire event, enabling more effective wildfire response and contributing to over 80% of potentially at-risk homes being saved during the Waldo Canyon Fire.

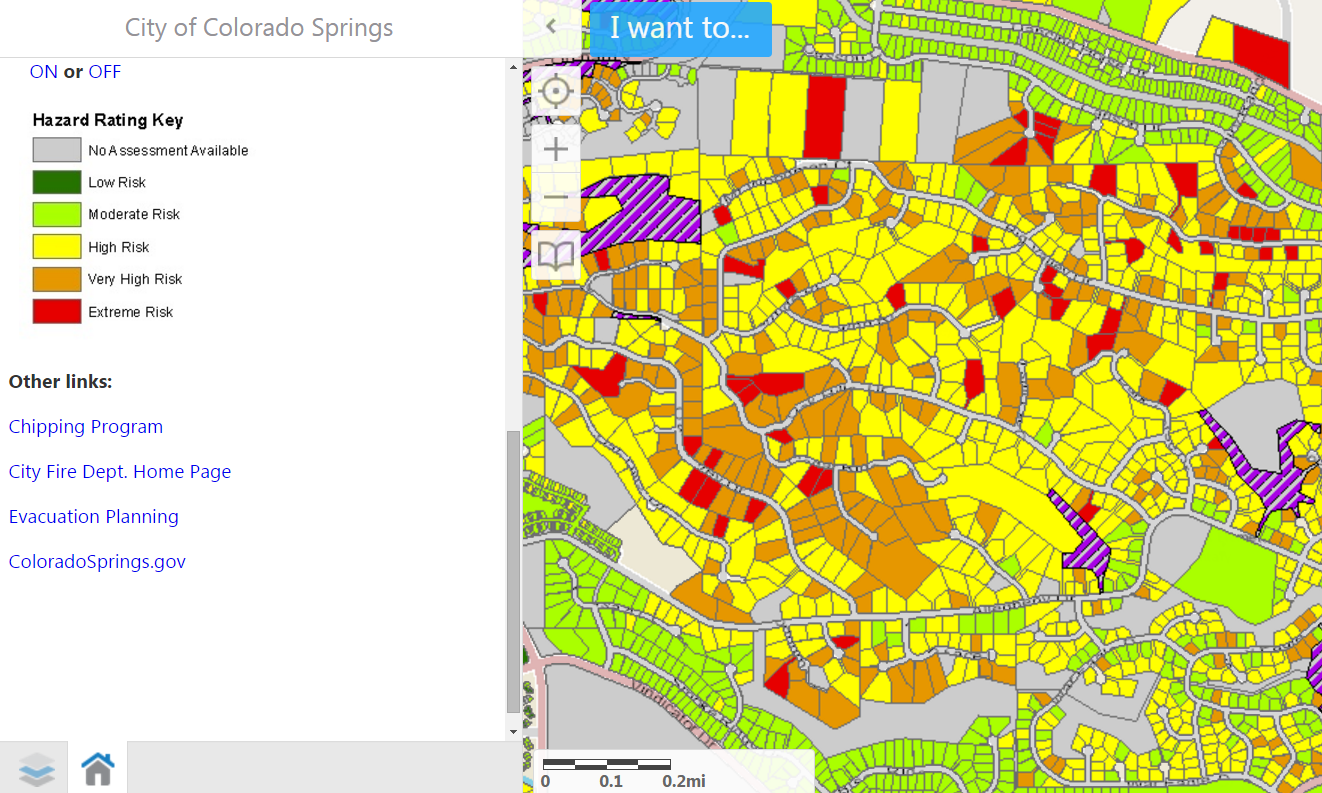

The Colorado Springs Fire Department had been working on wildfire risk assessment and mitigation efforts for years prior to the Waldo Canyon Fire. As early as 1993, the City passed an ordinance on vegetation management, roadway width, and sprinkler installation (applicable to development occurring after April 1993), and has subsequently adopted additional ordinances to strengthen building and construction occurring in the wildland-urban interface. The City’s first Wildfire Mitigation Plan was completed in 2001; meanwhile the Colorado Springs Fire Department Wildfire Mitigation Section began using the Wildfire Hazard Risk Assessment (WHINFOE) tool to determine risk ratings from low to extreme. Nearly 36,000 homes in 63 neighborhoods were identified as at-risk in the wildland-urban interface. An online public mapping tool was developed to display fire hazard ratings and a risk category for each property, with additional details such as distance between structures, predominant roofing and siding material, defensible space around the structure, and vegetation density.

Creating and maintaining accessible wildfire risk assessment information has proved useful in multiple ways:

- Homeowners were very responsive to the online website— it increased awareness and engagement.

- The site fosters proactive mitigation actions prior to any wildfire event occurring.

- The level of information available to practitioners has also facilitated greater learning after the wildfire.

A post-fire assessment team, led by the Insurance Institute for Business and Home Safety, observed where mitigation strategies were effective during the Waldo Canyon Fire by conducting home assessment surveys. The results showed less damage to homes that had employed mitigation strategies such as reducing fuel loads, spacing structures appropriately, and including landscaping breaks to prevent spread. The pre-fire data provided invaluable information for comparative post-fire damage assessments, and enabled wildfire practitioners to glean insights on wildfire mitigation. Finally, promoting awareness and partnerships through the risk assessment process complemented the success of many other mitigation efforts, such as the development of a Community Wildfire Protection Plan, grant funding and administration, adoption of progressive code requirements for new construction, and fuel treatments.

Developing and implementing a CWPP has many advantages for a local community, including:

- Provides the opportunity to establish a locally appropriate definition and boundary for the wildland-urban interface (WUI) and enables communities to identify local priorities and actions.

- Enables access to additional state funding opportunities (for example, CWPPs are an eligibility requirement for communities pursuing funds through the Colorado Forest Restoration program).

- Can assist communities in influencing where and how federal agencies implement fuel reduction projects on federal lands and how additional federal funds may be distributed for projects on non-federal lands.

- Reinforces existing stakeholder partnerships and establishes relationships among a wide variety of non-traditional partnerships.

As is the case with many specialized local plans, there are also a few common challenges:

- Can become “one more plan” for stakeholders to put on their to-do list, and the burden of implementation may fall unevenly on a few individuals. To address this challenge, some communities now include their CWPP as a chapter or appendix to their local hazard mitigation plan. This ensures adoption and maintenance, and can provide additional leverage for funding support.

- Depending on the scale, scope, and level of detail, CWPPs can be time-intensive and costly to develop. Can require specialized knowledge to develop that may not exist in local agencies.

- Creating a plan does not necessarily guarantee actions will get funded, although this can be addressed more effectively when coordinated with other community plans and priorities.